Rare occurrence of an inflight fire leads to setting a

higher materials flammability standard

FRANCES FIORINO/NEW YORK

Swissair Flight 111

leaves a valuable safety legacy: Investigators were able to

review aircraft flammability standards and improve testing and

certification of materials. It also leaves a painful legacy:

The lead investigator says there wouldn't have been an

accident if flammable materials hadn't been positioned next to

arcing wires.

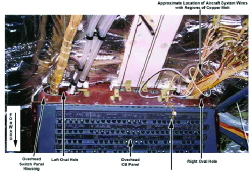

Flight 111 investigators found regions of wire copper

melt in the fire initiation area. The fire likely started

with electrical arcing "involving one or more wires."

Flight 111 investigators found regions of wire copper

melt in the fire initiation area. The fire likely started

with electrical arcing "involving one or more wires."

|

According to the Transportation Safety Board (TSB) of

Canada's final accident report, the inflight fire that led to

the Sept. 2, 1998, crash of the MD-11 had "most likely started

from an electrical arcing event that occurred above the

ceiling on the right side of the cockpit near the cockpit rear

wall" (see photo above).

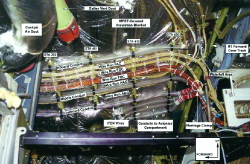

The arcing of one or more wires in turn ignited the

flammable cover material--metallized polyethylene

terephthalate (MPET)--on nearby thermal acoustic insulation

blankets (see photo, p. 63). A segment of arced electrical

cable from the inflight entertainment network (IFEN) is

believed to be associated with one or more of the arcing

events.

However, the TSB was unable to conclude whether arcing of

an IFEN wire was involved in the initial fire event. Other

flammable materials in the area, including silicone

elastomeric end caps and metallized polyvinyl fluoride

insulation blanket materials, helped to sustain and propagate

the fire.

Deteriorating conditions in the cockpit resulted in the

pilots losing control of the aircraft, which plunged at a

speed of 300 kt. into the waters 5 naut. mi. southwest of

Peggy's Cove, Nova Scotia. All 215 passengers and 14

crewmembers died in the crash.

The FAA's June

2000 airworthiness directive gave operators five years to

remove flammable MPET materials from MD-11s.

The FAA's June

2000 airworthiness directive gave operators five years to

remove flammable MPET materials from MD-11s.

|

It took the TSB 4.5 years, C$57 million ($38.8 million) and

up to 4,000 people at one stage to complete the investigation.

Recovery, sorting and cataloging of the wreckage took 18

months. Divers, a heavy ship barge and remotely operated

vehicles (ROVs) retrieved about 2 million pieces of wreckage,

or 98% of the aircraft (measured by weight) from 200-ft.-deep

waters.

When recovery was complete, investigators set out to piece

together the events that unfolded during the flight's final

minutes:

Flight 111 departed New York JFK International Airport at

8:18 p.m.local time on Sept. 2, 1998, en route to Geneva.

About 53 min. later, when the MD-11 was at Flight Level 330

(33,000 ft.), the first officer reported an unusual odor in

the cockpit, and there was a small amount of smoke visible on

the flight deck.

Both pilots concentrated on trying to determine its cause,

instead of expediting plans to land immediately, according to

the report. At 9:14 p.m., when the aircraft was about 66 naut.

mi. southwest of Halifax, the crew informed Moncton Control

Center of smoke in the cockpit and issued a "pan, pan, pan"

message. Controllers suggested Halifax International as a

diversion airport instead of Boston.

Meanwhile, failed end caps on air-conditioning ducts fed a

steady supply of air to the fire that raged in an inaccessible

area, while smoke and fumes seeped into the cockpit.

The aircraft was cleared to proceed directly to Halifax and

descend to FL290 from FL328 when it was 56 naut. mi. from

Halifax Runway 06.

The crew, who had donned oxygen masks, was focused on

dealing with a diversion to an unfamiliar airport at night,

and the approach charts to Halifax were not within easy reach,

according to the report. The aircraft's descent rate increased

to 4,000 fpm.

Aircraft checklists did not deal adequately with smoke

conditions, according to the TSB. The report notes that during

the lead arcing event, the associated circuit breakers did not

trip. No fire suppression equipment was near the area, and

there was no integrated inflight firefighting plan in

place--nor was there any regulatory requirement for either.

The accident report points out that the crew was

"essentially powerless to aggressively locate and eliminate

the source of fire or to expedite plans for emergency

landing."

The crew declared an emergency at 9:24 p.m. This was

followed by a series of electrical and navigation equipment

system failures. The cabin crew indicated electrical power was

lost in the cabin, and flashlights were being used to prepare

for emergency landing.

When the primary flight displays failed, the crew had to

adjust to small standby instruments, which added to the

workload (AW&ST Jan. 7, 2002, p. 43). Gradually overcome with

heat and fumes, the pilots lost situational awareness, and the

MD-11 crashed into the sea at 10:31 p.m. The report notes that

although the crew recognized the necessity for a diversion,

they did not believe the threat to the aircraft was sufficient

to declare an emergency or initiate an emergency descent

profile. The report notes that from the time the peculiar odor

was detected, "the time required to complete an approach and

landing to Halifax . . . would have exceeded time available

before the fire-related conditions in the cockpit would have

precluded a safe landing."

ACCORDING TO Investigator-in-Charge Vic Gerden, "One

of the most important aspects of this investigation was our

examination of the flammability standards and the flammability

of various materials. It is rare to have a fire on board a

large commercial aircraft, and we were able to glean a lot of

information about the materials and look to the tests used to

certify those materials. Without the readily flammable

material in this airplane, this accident wouldn't have

happened."

Among the 11 causes and contributing factors, the TSB found

materials flammability as the "most significant deficiency"

uncovered in the most complex aviation safety investigation it

had ever undertaken.

The Flight 111 final report also said the certification

testing procedures, mandated by flammability standards in

effect at the time, were "not sufficiently stringent or

comprehensive to adequately represent the full range of

potential ignition sources." Nor did the procedures mirror the

behavior of materials installed in combination, at various

aircraft locations and in "realistic" operating environments.

"The lack of adequate standards allowed materials to be

approved for use in aircraft, even though they could be

ignited and propagate flame."

The report said two factors shaped those standards. In the

mid-1970s, the FAA concentrated its fire prevention efforts on

improving cabin interior materials and setting higher

standards for materials in designated fire zones--with lower

priority given to fire threats in other areas. The

non-fire-zone hidden areas were viewed as not having potential

ignition sources and flammable materials, two elements

required for a fire, according to the report.

Canada's TSB alone issued 23 safety recommendations, along

with myriad safety advisories and information letters. The

board's latest recommendations, which were issued with the

final report, address the testing and flammability standards

of in-service thermal acoustic insulation materials. They also

call for taking extra measures in the certification of add-on

electrical systems and setting industry standards for circuit

breaker testing. The TSB also has proposed improvements to

capture and store mandatory and non-mandatory flight data, as

well as the installation of cockpit image recording systems.

Previous recommendations included a call for wire

inspections, the removal of MPET from aircraft, and

development of new flammability testing criteria. They also

urged that crews be provided with additional guidance material

to deal with smoke situations, and that checklists be

modified.

A number of safety actions have already been taken. The

FAA's June 2000 Airworthiness Directive ordered operators to

remove MPET from aircraft. The AD, which affects Douglas

heritage aircraft along with the MD-11, gave operators five

years to comply--and this means the flammable materials will

remain installed on in-service aircraft until 2005.

The FAA also conducted a review of problems in the MD-11

service life and developed a plan to correct wiring

deficiencies, which a Boeing official said essentially calls

for a re-rigging of wire systems. The FAA plan includes 61

final-rule ADs and 59 NPRMs (notices of proposed rulemaking).

The agency also started the Enhanced Airworthiness Program for

Airplane Systems for increased awareness of wire system

degradation and improvements in wiring maintenance.

There's still work to do, said Gerden. "Now it's our job to

ensure that follow-ups on safety actions are taken."

See Also:

İApril 14, 2003, The McGraw-Hill Companies

Inc.